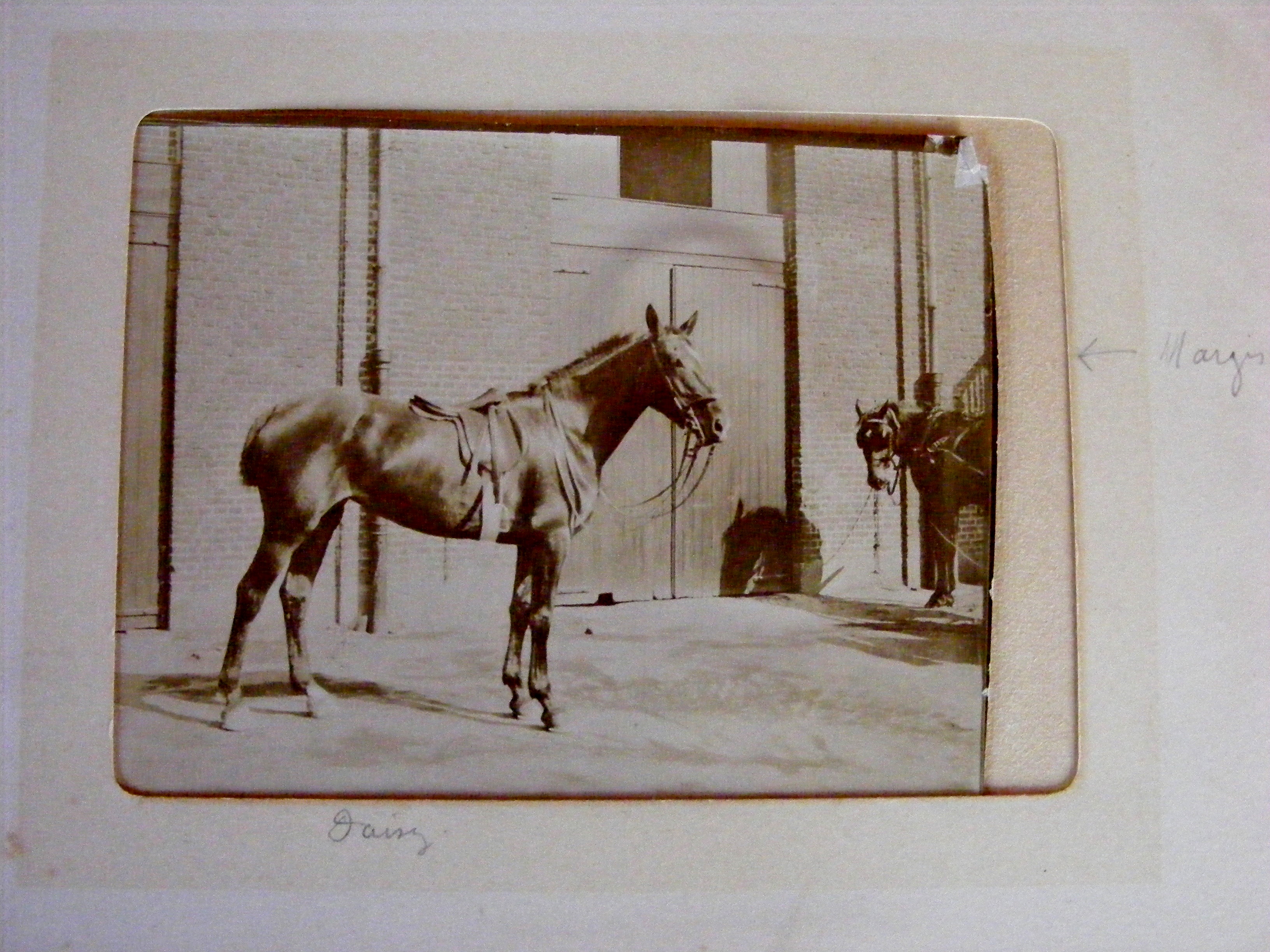

Anyone who has read Major Tom’s War will ‘get’ how important my forebears are to me.

Like Tom, my grandfather, I had an unsatisfactory father. When I was six or so Mum gave up on her philandering husband and packed me into her Austin A40 (together with a witless Dalmation named Bobby, the family portraits and almost all the photograph albums – the one of Tom and Evie’s wedding she left propping open the door of the marriage she fled).

We turned our noses Highlands-ward. She had family on the Black Isle. I had never been there.

The journey took three days, via various compassionate friends. I got lost on a housing estate in Manchester and was miraculously found by Bobby (so not an entirely dim dog then). We took on more oil than petrol, since the Austin dribbled a leak.

It got colder. Then it snowed. It was the winter of 1968. We drove through Drumochter behind the snowplough, arriving at Drynie in a blizzard as Jack Russells bounced and barked at my aunt’s windows.

Although I have lived both in England and Europe, the Highlands have been home home ever since. I tend to regard my English place of birth as an unlucky quirk of fate.

And the Black Isle is where Mum died, on the 5th October 2005. No-one forgets the day their mother dies.

And yet, somehow, even in those first hours after it had happened, I knew she was not altogether lost. Something of her remained, and that something was, and is, indestructible.

From time to time I become aware of her presence, usually when I am alone and out of doors, or driving. I would hesitate to call it Soul, although it is both bright and beautiful. Energy perhaps comes closer. The author Sally Vickers describes it as a sheerness of presence.

Mum comes to visit me less frequently now, as perhaps she feels I need her less as time passes. But travelling back from Orkney this morning, I realised with a strange flutter of the heart that she was there once more. A whisper remembered or half-heard. Why not go a different way… where does this road go? Shall we? Oh yes, why not, let’s!

So I eschew the direct route home, the NC500 camping cars and roadworks of the A9, for the empty and undulating 40 miles of passing places on the Melvich to Helmsdale road through Forsinard Flows.

A sigh of contentment as she settles in for the journey.

I should have driven straight past the RSPB visitor centre – and do so at first – but then I hear the faintest sound of disappointment from the passenger seat. I find myself undertaking a many-pointed turn in the road.

The interpretation has changed since I produced the last iteration for RSPB back in the early 2000s (fun facts about carbon sinks, zzzz). I like what is there now rather better.

I should have left it at that, of course. A quick look round. Instead my legs, atrophied from too much recent computer work, found themselves striding out through the peatlands. The coiled outlook tower on the horizon resembles a broken stump of fossilised bogwood.

Oh Mum, I say. For goodness’ sake. It’s raining.

You are not made of sugar, comes the familiar response.

I give in.

The peatbog has a delicate, speckled skin of life topping chocolatey depths as the heather and moss decay into aeons of fragrant peat, gobbling up carbon and keeping it safe.

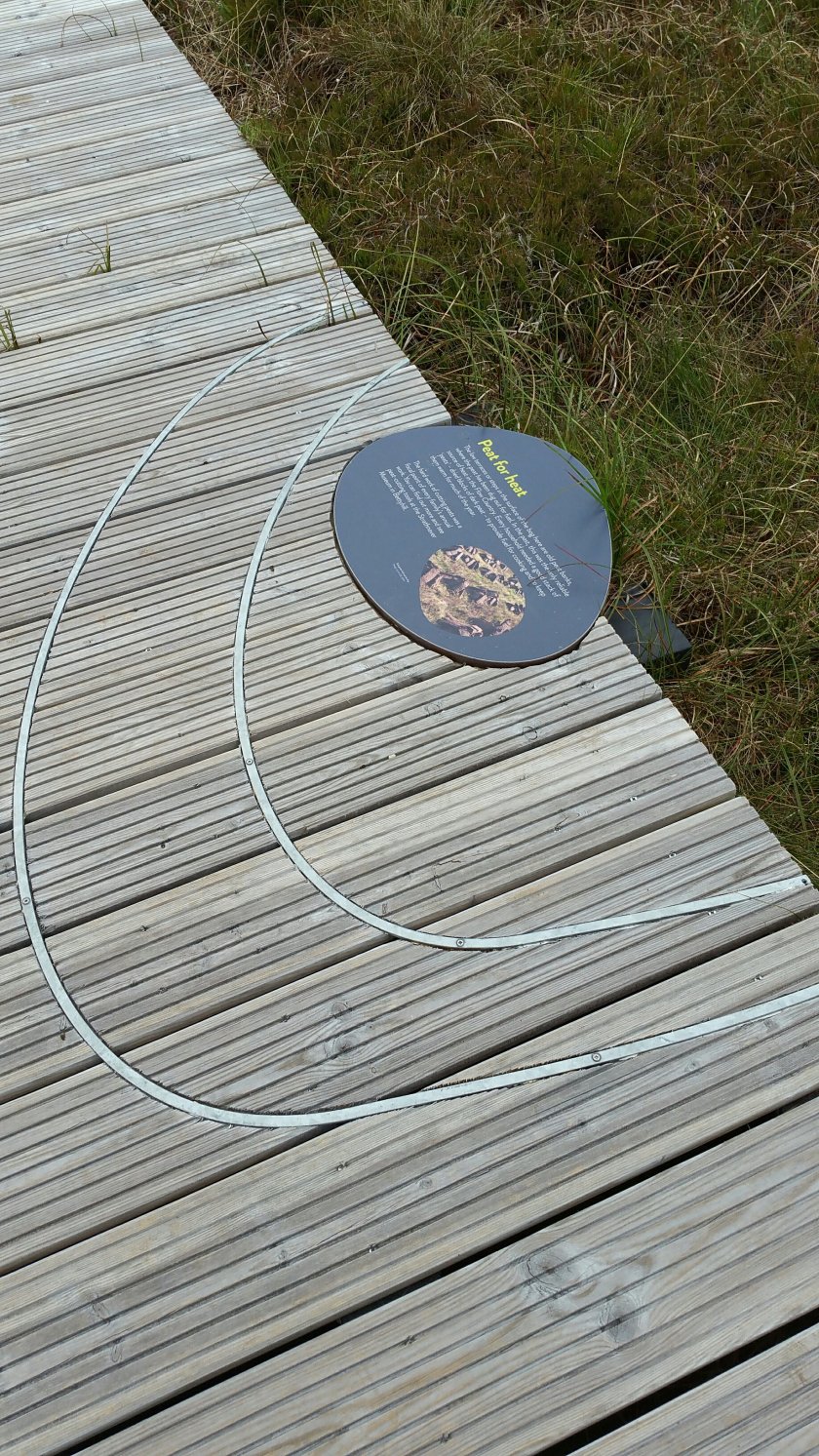

A duckboard path winds to the new tower. The path floats over the sopping peat on unobtrusive black recycled plastic sleepers, keeping the wood above water even in the wettest winter. Clever stuff.

I find myself slowing down, breathing more deeply, forgetting about the sixty-odd miles still ahead.

I stop and stare at the sphagnum moss, in all its shades of emerald and gold and crimson. Something about sphagnum reminds me of vividly undiluted jelly cubes, or perhaps it is just the ancient quiver of the peat beneath that I recall: the old flagstone paths once quaked here where one trod.

Bog cotton flickers. A cold wind is rising from the grey hills beyond.

Forsinard was nicknamed Frozen’Ard by troops on the Jellicoe Express heading north. Not much better today, and it is June. Midsummer. Climate change?

Sssh, says Mum. Don’t spoil it. Look!

Too sluggish to escape my lens, sand lizards are doing their reptilian best to bask on the exposed ends of the plastic sleepers. One big chap has lost his tail and I wonder how.

A heron, says Mum.

Another lizard, darker, with an elegant striped tail, is perhaps an expectant mother full of little leathery eggs. Protecting herself if not the future of her species, she is flattened against the plastic, desperately trying to blend in as she warms herself.

We watch her bright eyes, her tiny flickering breaths. She watches us right back, praying that her camouflage works and that we will not dart at her with a dagger bill to swallow her whole.

How do you think she sees us?

Two unfathomable gentle giants, we smile and leave the little dinosaur to rest, in peace.

When Mum walks with me, my vision becomes doubly acute. I can see every fragment of lichen-crusted peat, every wisp of heather and sweet bog myrtle.

I say their names out loud, threading my mother a string of millefiori beads as we walk: milkwort, tormentil, sundew, chickweed wintergreen (oh, look, look, a carpet of little stars…).

I return to the car refreshed.

On the drive south somewhere between the reserve and Helmsdale, as the light changes from inland grey to brighter coast, she takes her leave. I feel her go: the faintest pressure of her hand on mine as I change gear.

I would never say don’t go, and I try not to think it, for if she did not, I might never again feel her return: and that is unthinkable, for her occasional presence is a joy and a wonder to me.

Where does she go? To be with my brother, somehow, I think. But that is a story for another time.

And for now I am safely home.

It does not always rain in Orkney – but sometimes it does. We tried another holiday there en famille 20 or so years ago when it rained for an entire fortnight, but still Orkney somehow draws me back. When the vast skies do clear there is nowhere more beautiful and uplifting to be on Earth. It makes my heart dance just to board the Pentalina at Gills Bay and cross the Pentland Firth.

It does not always rain in Orkney – but sometimes it does. We tried another holiday there en famille 20 or so years ago when it rained for an entire fortnight, but still Orkney somehow draws me back. When the vast skies do clear there is nowhere more beautiful and uplifting to be on Earth. It makes my heart dance just to board the Pentalina at Gills Bay and cross the Pentland Firth. I am ashamed to admit that I only attended my first St Magnus Festival two years ago and I was doubly smitten. It provided the hefty hit of immersive international culture I sometimes pine for in the mainland Highlands: I love Scottish music and culture too but once in a while I need more.

I am ashamed to admit that I only attended my first St Magnus Festival two years ago and I was doubly smitten. It provided the hefty hit of immersive international culture I sometimes pine for in the mainland Highlands: I love Scottish music and culture too but once in a while I need more. The Festival, founded by composer the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, is now in its 43rd year. It is also truly international: not just performers but also many of the audience come from all over the world.

The Festival, founded by composer the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, is now in its 43rd year. It is also truly international: not just performers but also many of the audience come from all over the world. On Sunday I spoke in the plush cinema at the ‘Picky’ centre – rather a good turn-out – perhaps they thought I was one of the other guest speakers?

On Sunday I spoke in the plush cinema at the ‘Picky’ centre – rather a good turn-out – perhaps they thought I was one of the other guest speakers? This time my volunteer ‘victim’ was the lovely Martin, a devoted St Magnus Festival fan of ten years’ standing who comes up from Lancaster every summer. Yes, Reader, I executed him, but he was very nice about it and we shared a fudge brownie afterwards.

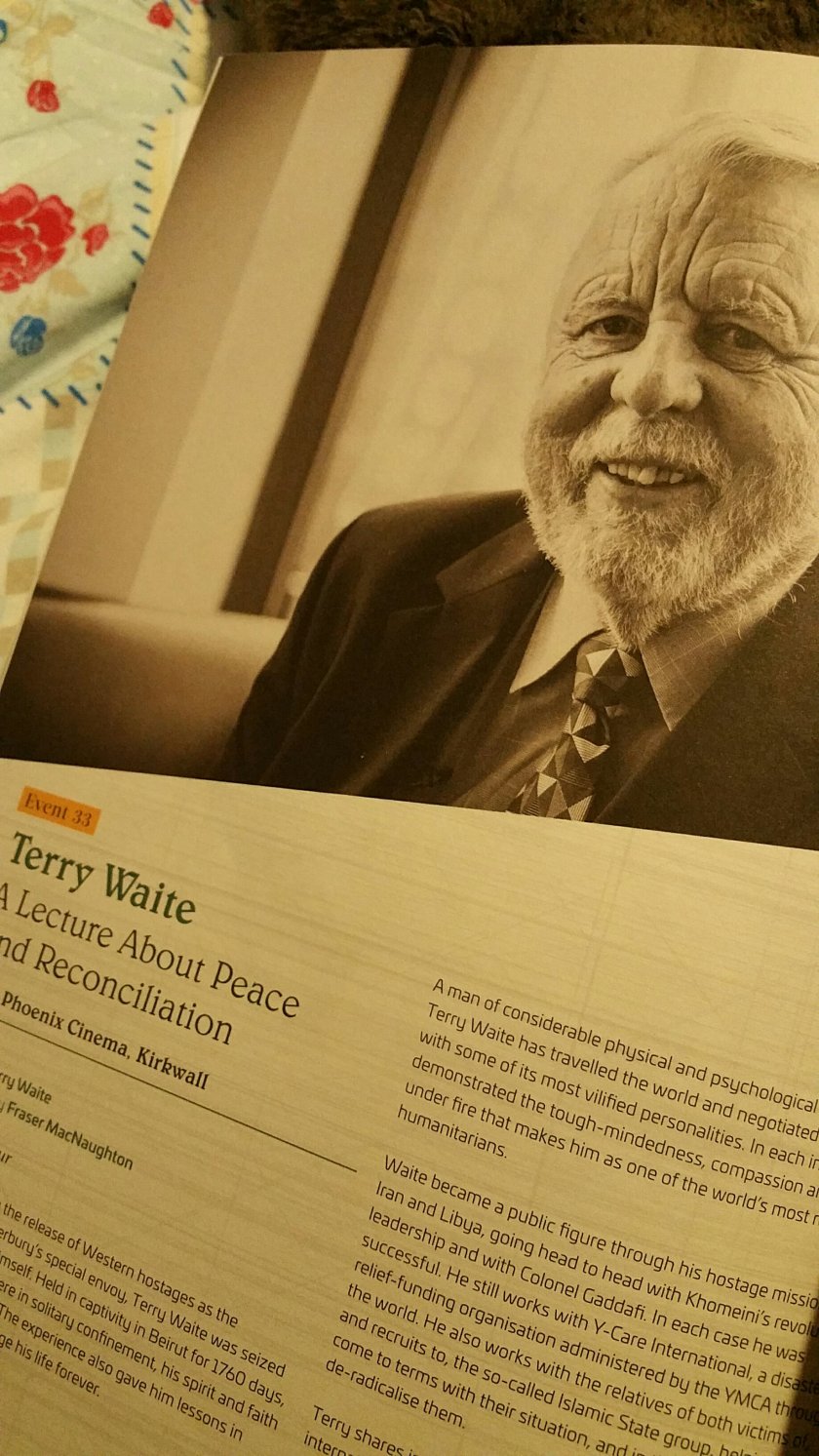

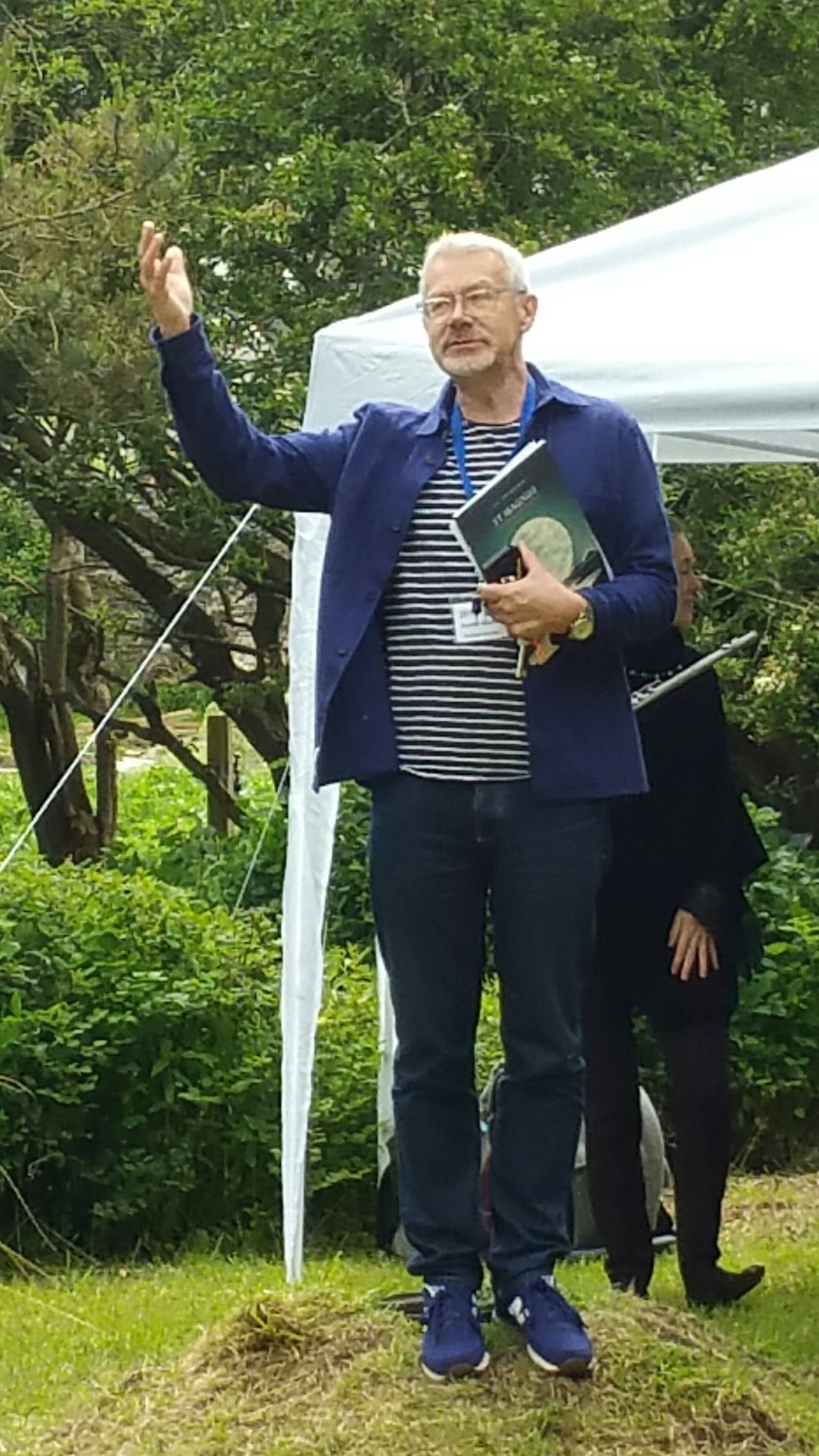

This time my volunteer ‘victim’ was the lovely Martin, a devoted St Magnus Festival fan of ten years’ standing who comes up from Lancaster every summer. Yes, Reader, I executed him, but he was very nice about it and we shared a fudge brownie afterwards. And oh yes, I did indeed check whether Terry Waite was in the audience before this photo was taken.

And oh yes, I did indeed check whether Terry Waite was in the audience before this photo was taken.

Here is a glimpse of the Peace Gardens Trail which enabled us to explore Papdale Walled Garden, Happy Valley (an inspired place to use!) and Woodwick House with a variety of musical and artistic interludes. At the end, a violinist and percussionist on vibraphone played Spiegel im Spiegel with sunlight and birdsong streaming through the upper windows and I sat there listening with tears rolling down my cheeks – I know it doesn’t take much! – but a blissful release from a stressful few months of work.

Here is a glimpse of the Peace Gardens Trail which enabled us to explore Papdale Walled Garden, Happy Valley (an inspired place to use!) and Woodwick House with a variety of musical and artistic interludes. At the end, a violinist and percussionist on vibraphone played Spiegel im Spiegel with sunlight and birdsong streaming through the upper windows and I sat there listening with tears rolling down my cheeks – I know it doesn’t take much! – but a blissful release from a stressful few months of work.

Poet Robin Robertson, author of The Long Take read from his poetic work.

Poet Robin Robertson, author of The Long Take read from his poetic work. Its gnarly roots probe dark and uncomfortable places in Highland culture. Inspired by his lecture, I explored my own metaphor for the St Magnus Festival.

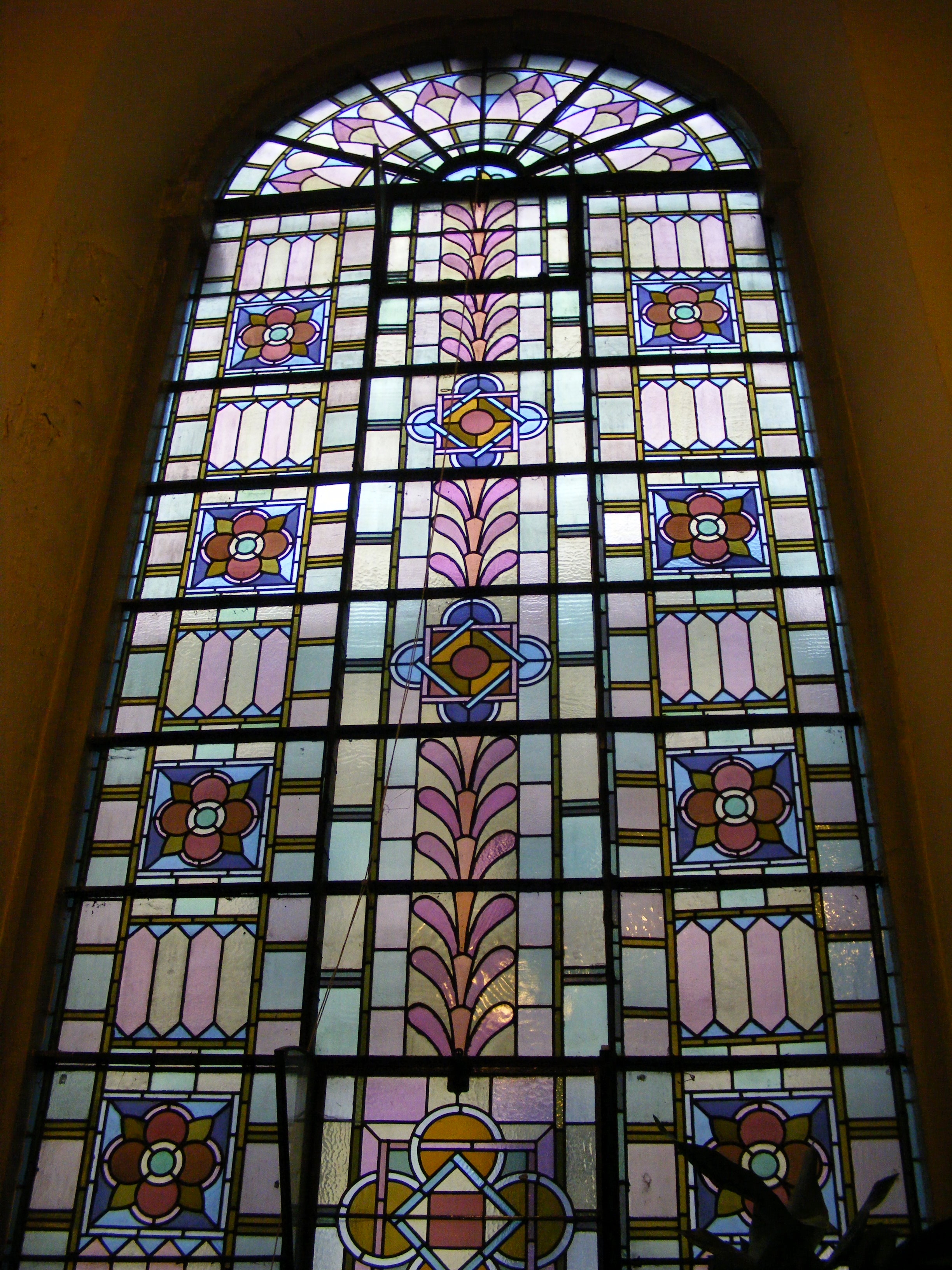

Its gnarly roots probe dark and uncomfortable places in Highland culture. Inspired by his lecture, I explored my own metaphor for the St Magnus Festival. At the end of the festival the tablecloth is removed, shaken, folded and carefully put away until next year. The memory of it resonates, just as the single notes of the haunting James MacMillan piece I heard performed today at the eery old Town Hall Kirk in Stromness still pulsed, long after the key was struck.

At the end of the festival the tablecloth is removed, shaken, folded and carefully put away until next year. The memory of it resonates, just as the single notes of the haunting James MacMillan piece I heard performed today at the eery old Town Hall Kirk in Stromness still pulsed, long after the key was struck. The annual miracle of St Magnus is brought about by an army of volunteers, a quirky selection of venues, some very good performers and the Festival team, led by Alasdair Nicolson, who was always destined for greatness (our paths crossed during our schooldays).

The annual miracle of St Magnus is brought about by an army of volunteers, a quirky selection of venues, some very good performers and the Festival team, led by Alasdair Nicolson, who was always destined for greatness (our paths crossed during our schooldays). My own personal highlights?

My own personal highlights? Tomorrow night’s performance of Alasdair Nicolson’s Govan Stones (almost but not quite its premiere).

Tomorrow night’s performance of Alasdair Nicolson’s Govan Stones (almost but not quite its premiere).