It was all Barbie’s fault. She made me do it.

For many of us who were ten years old in the early 1970s, our darkest repressed memories of cruelty and mutilation, if not actual murder, have been stirred up by the phenomenon that is the Barbie movie.

I had always hated traditional dolls, especially their slow, sinister eye-closing when tilted backwards. When (at the Bogroy Inn aged about six) I was told to hold a baby doll and sing a lullaby, I dropped it on its head. People laughed, but it was an act of protest, not an accident.

Golden Slumbers kiss my ***.

Sindy was still too much of a fat-head for me and so I shunned her: but when my eyes met those of Skipper across a crowded toyshop, I knew she had to be mine.

Marketed as ‘Barbie’s kid sister’, Skipper was like me: mouse brown hair, flat chested and flat-footed; something of a relief after her long-legged, wasp-waisted, pointy-boobed and arch-footed blondie big sister. Also like me, Skipper wore a dull blue flannelette nighty with lacy bits at the neck and cuffs, plus a sensible quilted dressing-gown for the Highland winter.

At first she had long hair, which I forgave her, but like all those early Barbie locks it seemed to have strayed from the Oppenheimer movie set, radioactively charged. Eventually all their hairstyles became crackling mushroom clouds of static fuzz. I quietly swiped Mum’s nail scissors to deal with that and soon Skipper, like me, had short curly hair, the shorn evidence stuffed down the back of the sofa. It was at that moment of personalisation that she became unique and mine, so all my Barbies followed the same trend.

The only thing I disliked about Barbie and Skipper et al were their ridiculous names. This was a serious friendship and I knew they could not possibly like their ‘box names’. They might wear gold and silver lamé bathing costumes and Flower Power maxi coats but they weren’t American to me. They were born – or unboxed, rather – in Scotland.

It never occurred to me that Barbie was short for Barbara (and in any case the only real Barbara I knew used to torture me behind the school shed). Mum suggested I should just rename them, but that didn’t seem respectful. These weren’t gormless baby dolls after all. They were sentient, real. And they had been sold in a box with their name on, whether they liked it or not.

And so they became my eternally-nameless companions, whom I thought of collectively as ‘Them’. I had, at one point, about seven of the Them, of whom just two (my short-haired mouse-brown Skipper and a shorn blonde Barbie, the latter still wearing the Most Beautiful Dress In The World) survive today.

At Peak Barbiedom there were two Skippers and four Barbies: some had knees that bent with an arthritic succession of clicks; some, rubbery arms that bent like they were hefting a pint until they broke at the shoulder through overuse to dangle uselessly at their sides; some, like the Barbie I kept, had a daintily angled head turn.

I truly loved Them. They were my only utterly dependable friends. I have kept two of Them for over fifty years, through over seven house moves.

How could I not, given the secret we share?

All looked sideways. None made eye contact. Nor did I. So He should surely have suspected something. There was only ever the one Ken, and he didn’t last long.

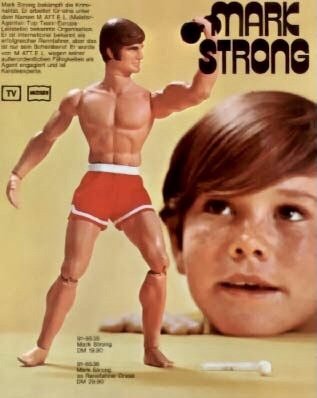

He wasn’t really a Ken, either. That was the thing. He was either a ‘Big Jim’ or a ‘Mark Strong’, I can’t remember which it said on the box (Mark Strong was I suspect the meeker British branding of Big Jim. Perhaps the latter would grow up to wear a bow tie and direct the British Museum, although he would need to ease up on the testosterone to manage such a transformation).

The real Ken was originally intended for boys to play with, not girls, but boys turned out to be ‘brand-resistant’, as some ashen-faced marketeer at Mattel probably pointed out in front of a chart showing his bombing sales figures.

Then Ken was launched in the UK as ‘Barbie’s boyfriend’, and every girl in Primary 7 at Inchmore School wanted him. At ten we were beginning to be curious about, if not actually interested in, boys. Our paths didn’t cross much with the real thing. They even had a separate shelter in the swampy school playground, just in case they contaminated us. No, none of the scowling, grubby, football-obsessed boys of Inchmore looked at all like the marketing pictures of Ken.

What wisdom might Barbie’s tall, handsome and mysterious new boyfriend impart? I had to know.

Mum bought my compliance for a trip to the dentist in Inverness (up the echoey stairs beside the station for a painful encounter with Mr Robertson or Mr Allan) with the promise of a Ken. Alas, once in the toyshop (Melvens? Pentangle?) we found they were clean out of Kens. I was more than a bit wobbly-lipped. I had had a jag and a filling and everything and not made a fuss, after all, and a deal was a deal. We only went to Inverness on the ferry a few times a year. A wasted trip was not to be countenanced.

Moreover, I had told my friends Jennifer, Wilma, Yvonne et al that I was going to get a Ken, so a Ken I jolly well had to have.

Then the kind lady said, ‘Ah, but these have just come in.’ She placed a plastic box on the counter. ‘Still Mattel, see?’ She pointed to the branding on the front.

‘Perfect,’ said Mum, lunging for him before I could really look. She hurriedly paid and handed the box over to me in the car with obvious relief. ‘See? Just the same. A Karate Ken.’ I tried to look enthusiastic, but I really wasn’t so sure. What I could see of ‘Karate Ken’ below his cheesy grin did not looked particularly enticing. And his name Wasn’t On The Box.

Would They take to him?

Kens and Barbies (I can’t quite say dolls – they were never dolls to me) were always held in place in their boxes by plastic-coated wires which it took a lifetime to undo. My ten-year-old self used to mutter ‘nearly there’ to reassure them as the fiddly process of release was brought about: I associated this with an awakening of sentience. But Ken/Mark/Jim or whoever he was looked positively delighted to be so confined and equally delighted to be released. I did not yet know or use the word vacuous but there it was in person.

He was wearing a white karate outfit surrounded by other manly karate accessories attached to the backing card with nylon threads as tough as cheesewire. It was never about the clothes for me, though. It was always a struggle to dress any of them in the garments they came with, the sleeves were so fiddly. Perhaps that is why so many shoebox outfits have survived in good nick for fifty-odd years.

I undressed him on the back seat of the car only to find that his rigid plastic hair was not the only thing welded on. So were his underpants. This was disappointing for some disturbing reason I could not yet pinpoint. His neck was bull-like and his head fitted over it, not on to it, so a hard seam showed. It looked rather as though he had been guillotined, then had his head stuck back on, but there was nothing of the suave French aristocrat about ‘Ken’. He was covered in very large, very rubbery muscles, had bizarrely articulated knees and a right arm that karate-chopped when you pressed a round panel in his back.

He was, to put it simply, gross.

Once home I wondered how I was going to introduce him to the massed ranks of my fun-loving tomboy Skippers and more glamorous and refined Barbies. I needn’t have worried. They took one look at him and my bedroom rocked with cruel laughter, for I had not spotted one last appalling detail in the car. This ‘fake Ken’ was for some mad Mattel reason made to a slightly smaller scale from the others. The Barbies were way taller than he was, and that wasn’t just because Barbie was strutting about on her impossible heels. I mean, everyone knew girls couldn’t ever ‘go with’ boys shorter than they were, for goodness sake! I could see They all hated him on sight.

Once Mum and I had started to watch Colditz, one of the meaner Barbies (who always wore the pink striped jumpsuit) pointed out that if I raised Ken’s arm above his head, then pressed the panel in his back, he gave a very creditable Nazi salute.

And that was the most interesting thing ‘Ken’ ever did. Almost.

I did take him to school once in the early days. Sharon (who had perfect hair and at least two real Kens) said, ‘That’s not a Ken.’

‘He is though!’ I blustered, knowing it was a lie.

‘No he’s not. He’s too short. And look, he’s all funny and lumpy. Yuck.’

I couldn’t really argue with that. I thought he was yuck too. ‘Ken’ was relegated to the bottom of my schoolbag. At home They began to pinch his dumbbells and try on his Karate gear, which fitted them rather better than it had him.

‘Ken’ lay abandoned in one corner of my toybox, his legs splayed at a vulgar angle. It was then that the plotting began in earnest. He might have cost my poor Mum hard-earned cash, but he was not one of Us. He had to go.

Our first attempt at permanent disposal was when I attached a home-made parachute to the naked-except-for-his-plastic-underpants ‘Ken’ with Sellotape and threw him up over the roof of our house. To my disappointment he failed to tumble down the chimney to become a writhing mass of hot plastic on the embers or to be snatched by a passing bird of prey. No, he made it right over the tiles, landing in an apple tree, from which my suspicious Mum disentangled his slowly spinning, still grinning form. When interrogated They – and I – said nothing.

Our final Wicker Ken moment came when Mum called us back down to the car. I looked at Them and They looked at me. We knew then without a word spoken that ‘Ken’ wasn’t coming home.

The final, fateful day of cold-blooded execution took place during a summer treat outing to a favourite burn referred to only as ‘up Strathconon,’ near a mighty bridge where sometimes we would swim. We loved to explore this burn. They would clamber up and up it, build dens in the heather, taking refreshing dips in the rockpools or sunbathing on the garnet-speckled granite outcrops wearing cool shades. Meanwhile Ken or Jim or Mark or whatever his bl**dy name was would just lie there, ape-like, in his plastic underpants, grinning at the sky.

As we walked back down the burn to Mum’s Morris Traveller, ‘Ken’, his arm still fixed in a Nazi salute, began to dive into the water just upstream of the many waterfalls en route. We would watch him plunge over and downwards into the depths, before bobbing to the surface with that repugnant smirk. Then, at the highest, deepest waterfall, We took him by one leg and threw him in a spiralling arc high into the air. The setting sun caught his face and I will swear to this day that there was the faintest tremor about his perky lips as he smacked the smooth, peaty water above the falls. The Barbies sniggered. We caught a flash of his red plastic underpants as he shot over the edge to plunge down, down, down into the darkly frothing water below.

He never came up again.

I looked at Them. They stared back in mute defiance. I gave a desultory poke about in the pool below the falls with a broken stick, just so I could say I had looked, but Mum was calling again. Collective feminism personified, we turned as one our backs on that smug plastic interloper – and condemned ‘Ken’ forever to his watery grave.

Perhaps someone else found and rescued him. Perhaps he is still down there somewhere, bravely leering through the slime. And although over the years I have returned to the same picnic spot up Strathconon many times, it is never, ever, without a tiny, thrilling, shiver of guilt.

Did you have a Barbie, a Skipper or a Ken? Feel free to share this post if so…

Vee Walker is an author and editor based in the Scottish Highlands. Her prizewinning archived-based novel of WWI, Major Tom’s War (an adventurous love story) is available in paperback and ereader editions from Kashi House 👇.

https://www.kashihouse.com/books/major-toms-war-paperback

https://www.kashihouse.com/books/major-toms-war-ebook