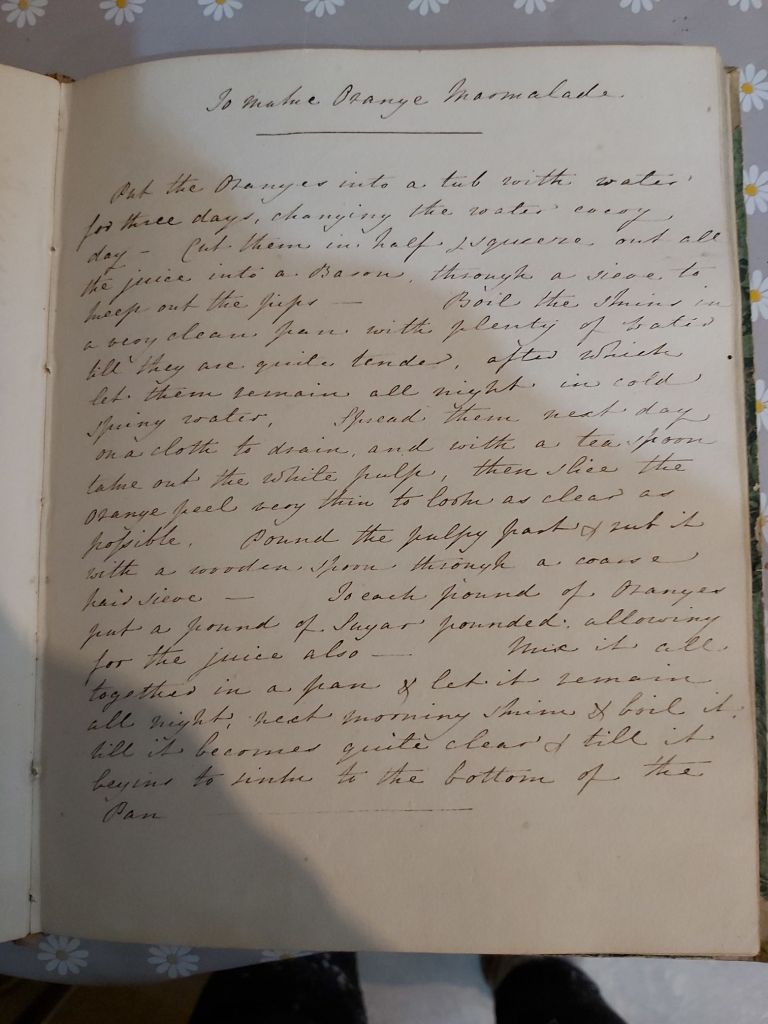

Back in 2011, my first ever publication (long since out of print alas) was The 1810 Cookbook, a new edition of a recipe collection pulled together by Jane Onslow, my 4 x great grandmother, on the occasion of her marriage to Edward Winnington-Ingram in 1810. It is long since out of print but I still use the original to cook from. And one of the best recipes it contains is for this Seville Orange marmalade. Jars of pure sunlight.

The W-Is were church gentry – and Jane, daughter of the Dean of Worcester, whose portrait suggests she enjoyed fine dining, moved with Edward into the family stately pile, Ribbesford House, which is currently for sale if you have a spare million and three times that as a restoration budget! 👇

Ribbesford House, Ribbesford, Bewdley | Property for sale | Savills https://share.google/T7QMse0KDveMhOcOG

Jane’s recipe collection shows how widely they sourced their food: macaroni ‘as at Naples’, Curaçao, curry powder, mock turtle soup, macarons and crême brulée for example.

To make this marmalade you will need a spare week, about 20 Seville oranges, an ample supply (3kg or so) of granulated sugar, plenty of good tapwater, a large preserving pan, a ladle, a spurtle or long wooden spoon (check it does not smell of onions), a jam funnel and a basin – or a handy clean bathtub!

In 1810 oranges from Seville would have been picked green and ripened in the holds of sailing vessels. Sevilles are small, rather dull fruits, never sold with the preservative wax which generally make an orange shiny today. This also means the fruits do not last as long, so marmalade season begins in December and will be over before the month of January is out.

A ship’s hold was probably not the cleanest of places, which is why the recipe begins with rather a strange instruction to modern eyes: to soak the fruit in a basin for three days, changing the water daily. I use our guest bath, well scrubbed before and after, for convenience! If you do this, the different layers of the orange soften and much of the bitterness gets washed away. Even in these modern times, it is remarkable how many tiny specks of grit get released from the skins during this three day process.

On day four, rinse the fruit one last time, drain and remove all the ‘eyes’ (where the stalk was connected) with a sharp pointed knife. You may need to clean or cut around this area.

Now chop each orange in half around its equator. Squeeze the juice into a bowl and set aside. Strain any pulp from the seedy discard and add to the juice bowl.

Now chop the half oranges into quarters and place in a preserving pan. Cover with water and – yes, you’ve guessed it – leave to stand overnight. Taste this steeping water in the morning and it will still be bitter – these are not sweet oranges. Replace the water with fresh, covering the fruit. Bring to the boil, then simmer, covered, for about 20 minutes or until the zest yields to the tip of a knife but still has some resistance, but the pulp and pith are quite soft.

Place the quarters on trays and allow to cool and dry off overnight.

In the morning, scoop out all the pulp and strain it into the bowl of juice, then, with a sharp dessert spoon, scrape away and discard as much of the thick white pith as you can. You should now be able to see daylight through the skins.

Either with a sharp knife or with a pair of sharp kitchen scissors, cut these translucent zests into thin strips of varying lengths.

I use a big measuring jug for the next bit. For every jug of shredded zest and every jug of juice, add a jugful of sugar to the preserving pan. Set aside to allow the sugar to dissolve, in theory overnight, but this particular corner I cut. Jane’s sugar would have been grated from a sugarloaf cone, so might have taken all night to break down. The main thing is to keep stirring it and not start to heat it until all the sugar has dissolved into the juice.

Now prepare your pots and lids. I like to use the commercial vacuum method, not faff around with circles of cellophane and elastic bands (sorry SWRI!), so good quality recycled jars like Bonne Maman are ideal. I made marmalade with 5kg of oranges this year and used 20 jars as shown. I run them through the dishwasher first, then pop them on a big baking tray with sides, along with my ladle and jam funnel, in the oven at 100 degrees.

Back to your jam pan. Mine is a giant stainless steel pressure cooker base. You want a nice heavy bottom! I inch up the heat bit by bit until, after an hour, it comes to a rolling boil on maximum heat. Heat too rapidly and it will burn. Don’t be tempted to stick a finger in it to taste it, either, you’ll end up in Casualty!

At this stage the marmalade will be quite pale in colour and all the zest will be floating on top. Stir mixture frequently – I use a porridge spurtle.

Once a circle of yellow froth forms after about 20 minutes, skim off these impurities which will spoil the clarity of your marmalade (a good time to test the flavour, skimmings are delicious, impure or not!). Jane’s sugar probably had a few more impurities than Tate & Lyle does today.

After a final 20 minutes or so, watch for three magical signs: the liquid reduces and starts to set on the sides of the pan, the colour and sound of the mixture deepens, and the bubbles become more glossy. When a little of the liquid starts to wrinkle when dripped on to a cold plate and tilted, pull your pan off the heat right away.

Wearing washable or rubber gloves, ladle the hot marmalade into the hot jars. I added a nip of Scotch to part of my batch then poured the hot marmalade on to it. You can also add treacle and cut the skins more chunkily to make Dundee style marmalade.

Place lid on jar only loosely. Once all jars are filled and lidded, put tray of jars back in the oven for 15 minutes.

Tighten all the lids thoroughly and wipe any stickiness from jars. Allow to cool overnight – you’ll hear the pleasing ‘pop’ of the lids as the protective vacuum takes hold – then label and store. Will keep for a couple of years – if it gets the chance!

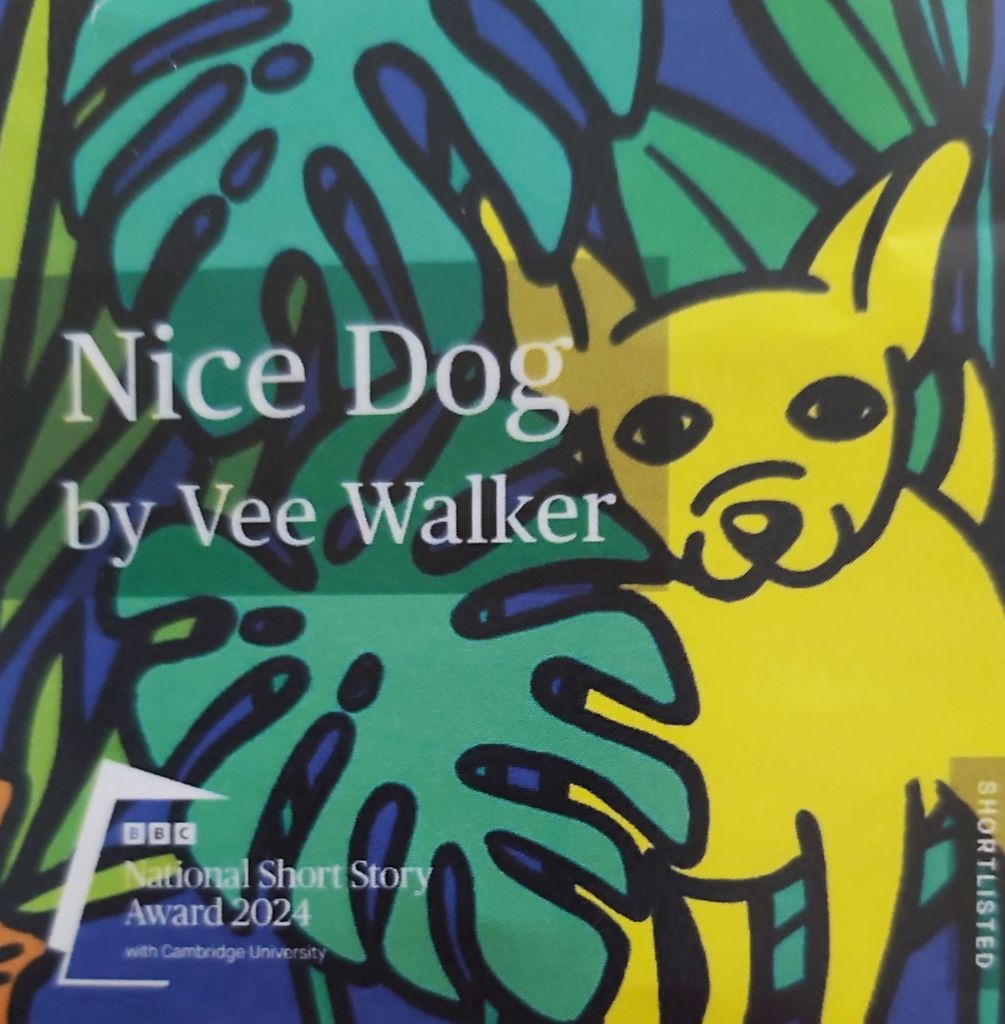

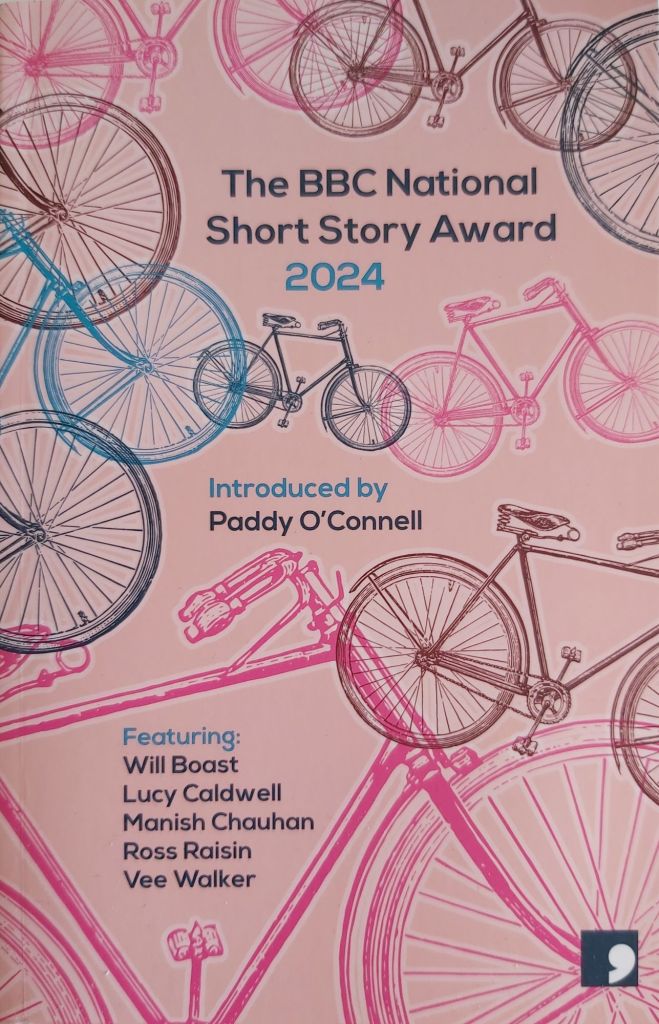

Thanks for reading this blog post. There are a few other recipes on here if you scroll back. Happy to answer queries and I would love to see pix of successful makes! I am on Threads as @veewalkerwrites and Facebook as Vee Walker.

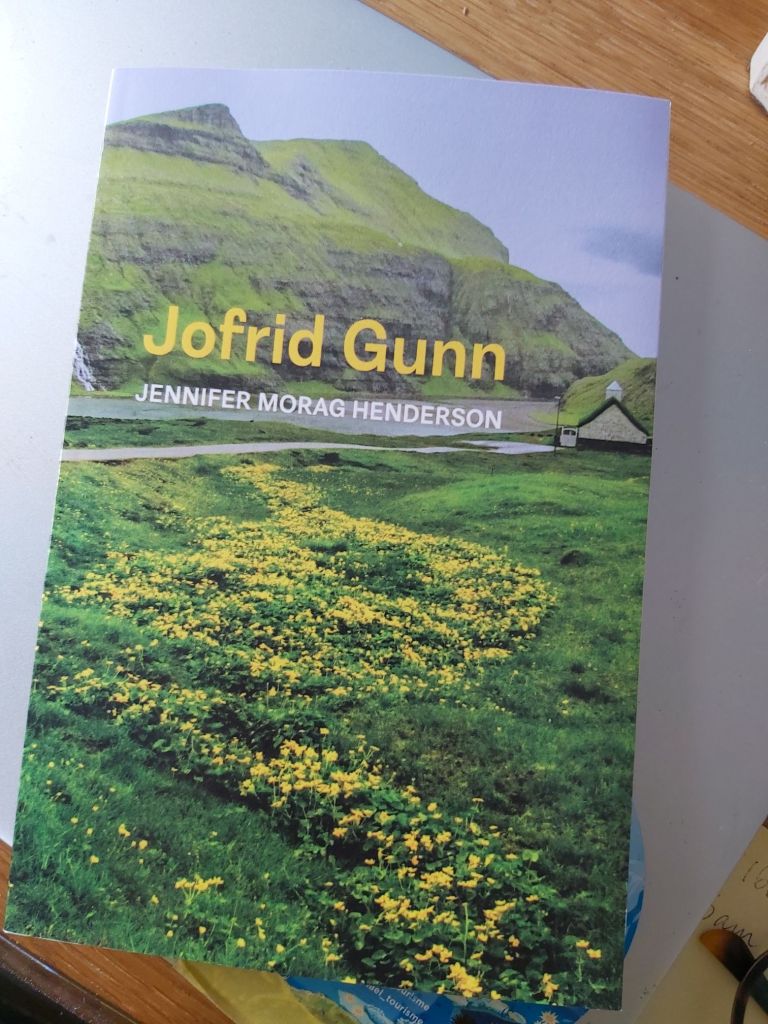

You can still buy my novel Major Tom’s War (a WWI love and adventure story based on real people, including descendants of Jane and Edward W-I) and events in paperback or ereader from http://www.kashihouse.com.

Here’s Jane W-I’s (cook’s, probably) original recipe, by the way 👇.

Happy marmalade-making!

Vee x