A short story by Vee Walker

The Feira do Livro in Madeira had been little more than an excuse to get away, as May Anstice’s literary agent, Millicent, had pointed out. ‘It’s only an hour’s gig, May. They want you to kick off with ten minutes of you reading in English, followed by some nice Portuguese chap reading from the translation, then a bit of chat. Blah blah, easy-peasy. Five days in the Madeiran sun. And they’re paying for your flights. What could be better?’ Her agent had then lowered her voice into what May recognised as its cajoling tone. ‘And you never know, May. You might find Madeira inspiring. It’s time you got away, really, after…’

After. It was still hard for others to say it, she knew; even harder for May to believe that her dull, kind and reliable husband of thirty years had, just a few months earlier and entirely unexpectedly, left her for the woman next door.

May also knew that the word inspiring on Milly’s lips contained more than a hint of a threat. Millicent Carter was one of the best agents in the business. It was now five years since she had launched May’s début novel Terrified, to critical acclaim. It was an epic historical romance set in the aftermath of the French Revolution – la Terreur – which had taken May blood, sweat, tears and seven long years of her life to write.

Terrified had done rather well for both May and for Milly. It had won a minor literary prize, and had subsequently been translated into several European languages – most recently, of course, Portuguese. Hence the trip to Madeira.

Five years is a long time in publishing and although May had begun another novel or two they had all somehow petered out. Publishing was a cruel business. She knew, too, that there were younger, fresher, authors hammering at Milly’s door every hour of every day, authors who were not middle-aged, stale and deserted. Her agent wanted more than she could give.

Terrified was rooted in May’s undergraduate days, studying at the Sorbonne in Paris. Which was of course also where she had met Malcolm, then an earnest PhD student ten years her senior. How could she replicate such intensity in another work? May was well and truly blocked, and even her beloved daughter did not seem to understand why.

Jonquille, known as Quills, had been so phlegmatic about her father’s departure for pastures new that May had suspected her of foreknowledge, which Quills flatly denied. ‘Look Mum, maybe there is a reason why this has happened? I love him, and I know you do, or did, but Dad can be deathly dull. God knows what this Geraldine woman sees in him.’

Geraldine Fawkes and her husband had been their neighbours: she then became a widow who wore her grief with elegance. May had even encouraged Malcolm’s kindness in the early days of Geraldine’s loss, never suspecting that it would lead to an outcome of this kind. She had believed Malcolm to be rather past that kind of thing at 60. He had certainly seemed to have been with May.

It had all been so steelily amicable. As far as everyone else – Malcolm and Geraldine and Milly and even Quills – were concerned, the transition seemed to be done and dusted. And yet May herself continued to relive that terrible day when, after their ritual morning coffee, Malcolm had simply mumbled a few words, picked up his ready-packed suitcase, pecked her on her pale, shocked cheek and moved in next door.

Whenever May saw the pair together (which was almost every day given the circumstances) they positively oozed happiness. Malcolm might look years younger, but May felt decades older. Oh, she could function in day-to-day terms but existed only on automatic pilot, with the words but he promised, he promised pounding at what remained of her heart. She felt unloved, dishonoured, uncherished and yet could tell no-one.

Her plane had made several hair-raising attempts to land in Madeira in the late afternoon, prompting passenger applause when the pilot finally made it down through the storm. As she drove into Funchal from the airport through a dark deluge so fierce she could hear the taxi driver praying aloud, May wondered why on earth she had agreed to come at all.

In the light of all this it would be hard to describe the brief Madeira book festival appearance of the once-bestselling author May Anstice as a wild success. She had even rashly agreed with Milly to speak on the evening of her arrival ‘just to get it over with’.

She found herself in a leaky open air tent being interviewed by someone whose English was so heavily accented that she struggled to make out his words above the din of rain on canvas. A sweet Madeiran youngster read from the new translation of Terrified rather better than she had in English. There were questions, of course, and polite scattered applause, but her audience had no cover and was cold and soggy. Her host kindly offered refreshments afterwards but she could hardly believe he was sincere in this weather and declined, pleading a headache. Instead she trudged through the wet streets (beneath a free bookfest umbrella) clutching the map showing the whereabouts of the apartment of Milly’s friend in Ribiero.

How typical of Milly, she thought, as (soaked in spite of the brolly) she scrambled crossly through the main door of the apartment block with her wheeliecase. Her agent had arranged accommodation through some contact instead of a nice hotel: Milly’s little black book was limitless. God knows what this place would be like.

May found the Residence Arriaga easily enough and had soon collected the key from the elderly porteira. There was a lift, thank God, she had feared the worst. The multiple mirrors reflected back a plump middle-aged face with grey eyes and bedraggled, wild hair. Was this the woman Malcolm had once loved, then come to hate? Little wonder.

The lock was a little stiff but the door finally opened to reveal a spacious and warm apartment. She found the bedroom and ignored the rest, stripping off her wet clothes and leaving them where they lay before getting into bed. Rather a comfortable bed, she registered, just before exhausted sleep claimed her.

She awoke to the sound of more water falling. Did it never stop raining in Madeira? Wrapping a white bath sheet around herself she padded across the polished marble floor to the window, preparing herself for the disappointment of the continued downpour. Instead she sighed with surprise as the warmth of a blue-skied Madeiran late autumn day embraced her.

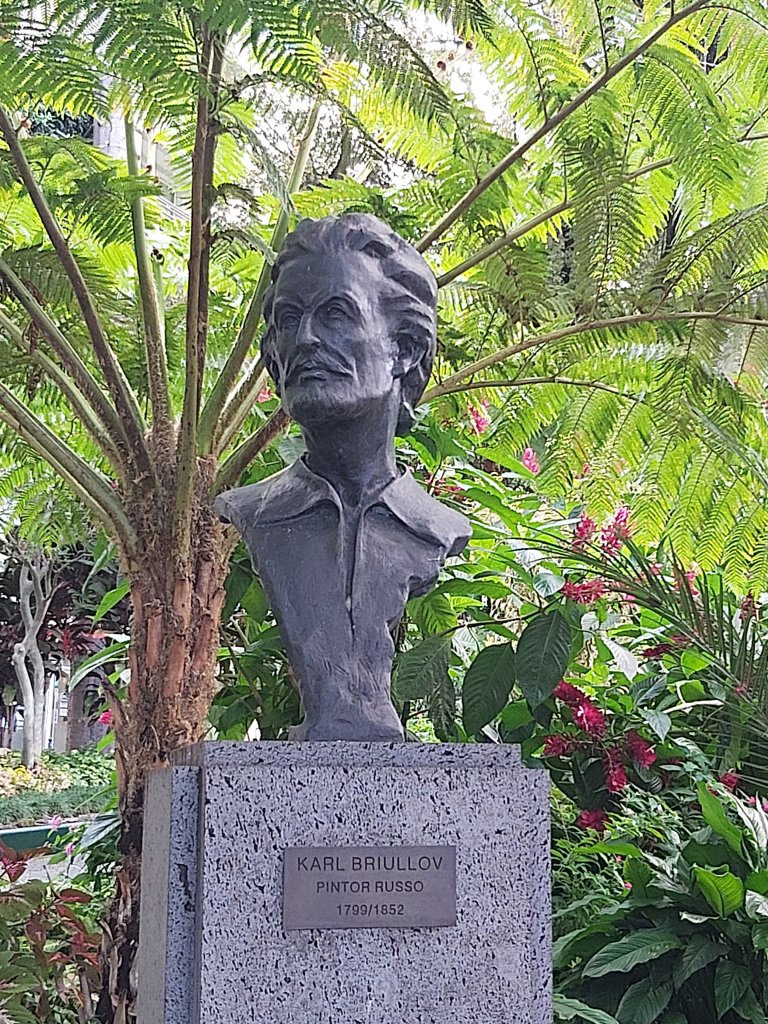

Below her lay what she would soon discover to be the Jardim Municipal – the Municipal Gardens. Palms swayed over an esplanade and tree ferns cast leafy shade over a pool where three large fountains now played. ‘Wow!’ exclaimed May, impressed in spite of herself. She had noticed none of this in the previous night’s downpour.

‘Welcome,’ read the sheet of notes on the kitchen work surface adjacent to a large bowl of fresh fruit. ‘Have a lovely stay. I’ve popped a few bits in the fridge. Lots to see and do, there are some brochures on the table. Your nearest eatery is the cafe in the park. Bom apetite!’

May, who seldom relaxed and normally lived out of a suitcase on work trips, surprised herself by taking time to unpack, placing her few possessions in the drawers and wardrobe. She then poured herself a large glass of orange juice from the bottle in the fridge and found herself drawn back to the unexpected view from the window. The juice was sweet and tasted fresh. Yellow taxis came and went, Madeirans bustled and tourists strolled in the street below. A tall, thin boy came flying round the corner from up the hill laden with cardboard boxes, whistling cheerfully, and disappeared among the lush greenery of the Jardim Municipal.

Once showered and dressed, and after checking three times that she had the key (Malcolm had always looked after their keys and passports) May went downstairs, this time avoiding eye contact with herself in the mirrored lift. Outside, the gentle sunshine made her gasp with pleasure – it had been just above freezing when she had left home.

She crossed the patterned cobbles to enter the gardens and as she did so, each step gave her the oddest sensation that beneath her feet, the tree roots somehow knew she was there, shifting like snakes deep within the red Madeiran earth. She found a corner table in the shade, still feeling conspicuously alone among the cheery couples and families.

The whistling boy she had noticed earlier approached her table holding a menu. ‘Something to drink, Senhora? Something to eat? You just arrive in Madeira? How long you are stay?’ She told him five days, asked for a black coffee and flicked through the battered menu, settling on a safely dull hamburger.

She thought the boy shrugged slightly as he took her order and when he returned with her coffee (which she sniffed appreciatively – Malcolm had always made their coffee) there was a shiny golden tartlet on the side. ‘I say, young man, I didn’t order this,’ she exclaimed, over-emphasising her very British gestures of error and rejection. If only she spoke Portuguese as well as she did French.

‘You not want? Is gift. My aunt Ana, she makes. Pastel de nata. Very tasty.’

‘Oh. Oh I see. Well, thank you. Please thank your aunt.’ She bit into the warm custard and crisp pastry. My word, but that was good. Three bites and it was gone.

The hamburger was perfectly acceptable when it turned up, if a little unexciting. She ate it more slowly, turning the pages of her disappointing airport novel for company.

‘May I?’ She started and looked up at the sudden voice. A COVID-masked man with silver hair and rather a military bearing stood before her, pointing at the second chair. Was she really so obviously British? She had no real wish to share her table, but the esplanade café was busy and so she gestured to him to take a seat.

‘Forgive me, but aren’t you May Anstice, the author?’ That surprised her into a smile, for few authors can resist the seductive lure of recognition. ‘Yes. Yes I am.’

‘Charles Hamilton.’ He extended his hand then turned it into an awkward knuckle bump. ‘Sorry. It’s so easy to forget about COVID here. I heard you read from Terrified last night. It was… well… terrific.’

May smiled at him. ‘It was terrifically wet,’ she said, with feeling.

‘Yes, that too.’ The young waiter brought him his coffee without being asked, May noted. The boy had added a jug of frothy milk on the side which he then poured into Charles’ cup: a regular, then.

Charles ignored the boy, all his attention on May. He removed his mask, smiled and sipped his coffee.

‘What an absolute stroke of luck, seeing you here,’ he continued. ‘Terrified is some book. I lived in Paris with my wife, years ago. Quite a city too, eh!’

May was reassured by his mention of a wife but still had no desire to outline her own personal circumstances to a stranger. She chose instead to ask him if he too was in Madeira on holiday.

‘Goodness me, no,’ he laughed, revealing good teeth. ‘I live here now. My wife and I arrived on board our yacht seven years ago and we never left. It is five years now since I lost her. Do you sail, Mrs Anstice?’

Which did he mean by lost, boat or wife? ‘I’m so sorry,’ said May, because that would do for either circumstance, adding, ‘No, I don’t sail. And do please call me May.’ Mrs Anstice felt a bit formal for the circumstances: especially now she was (technically) Mrs Nobody.

‘Pity. Wonderful sailing around Madeira.’ Ah. So it was the wife he had lost.

They made small-talk for a few minutes longer and then he stood and took his leave, pleading a phone appointment with his stockbroker. Just as he prepared to go, he seemed to think again and turned back. ‘Look, don’t think this too forward of me, May, will you, but would you care to have dinner with me tonight? There’s a nice little Madeiran-Italian place just over there behind the trees. Portaliano. See it?’

May saw it. She opened her mouth to say she really couldn’t possibly and yes came out of its own accord. They agreed 7pm. She watched as he counted out the exact cost of his coffee in coppers and looked at his expensive watch. ‘Where’s that blasted Diogo got to? Head in the clouds half the time. His uncle runs this little place. Probably nowhere else would have him.’ Charles left the coins on the counter and walked away, turning to raise his hand. May surprised herself by registering in that fleeting moment that blue-eyed Charles Hamilton really was rather a dish.

Once Charles had gone, voices were raised behind the bar. Diogo and his uncle were having a loud exchange of views and, May noticed, kept looking in her direction. She wondered with a flash of insight whether the little pastry had been Diogo’s own initiative. Perhaps his uncle was angry with him. She resolved the matter by leaving the boy a hefty 10E tip on top of the cost of her meal and started walking towards her apartment block, but at the edge of the park she heard footsteps running behind her. Clutching her handbag to her chest she turned to find Diogo waving the note. ‘O Senhora, forgive me, I not mean to fright you. Madeira is very very safe place, you know? But this, this is too much for tip.’ He pressed the 10E note back into her hand. Before she could explain he had darted back between the busy tables and was gone.

I have nothing to wear, thought May, back in the apartment. Her smart bookfest suit was still damp and a bit formal anyway. Nothing else she had brought was suitable, so she decided, on impulse and with mounting excitement, to go to buy a new outfit. Several hours of unaccustomed self-indulgence later she emerged from a boutique in a little arcade nearby with a rather lovely dress in flowing gold wool. It had a belted waist and soft, wide skirt and a smart wrap to match. Just the colour of that custard tart, she thought, as she eased the dress over her head and shoulders. It felt so good next to her skin. She felt good, for the first time in many months, even (if she were being honest) in many years.

The window kept drawing her back to its view of park and vertiginous landscape beyond. She saw that an exotic version of Christmas was starting to fill the Jardim Municipal. A white pigeon sitting on a wire overhead was trying to seduce a mate with a piece of golden tinsel which one of the decorations had shed on the way in. Giant red conical Christmas trees trimmed with hearts and bows stood out uneasily against the authentic tropical plants. Reindeer trotted across the café esplanade, pulling Santa’s sleigh. Diogo was helping someone in official overalls erect the roof of what could only become Santa’s grotto. And yet it was warm, as warm as a sunny summer’s day at home. May could feel herself unfurling in the heat, all rooted in the pleasure of her new frock and a chance encounter.

It did begin as a lovely evening. Charles was waiting at the restaurant door, smart in a dark suit. As he seated her in the window overlooking the eastern boundary of the park, she noticed he was wearing diamond cufflinks and was glad she had bought the new dress. The food was sublime – little savoury dumplings with a crisp filling followed by a madly daring squid-ink pizza for her; prawns and a steak for Charles. They drank a bottle of vinho verde, then another of vinho tinto. When she got up to visit the ladies she felt her head spin. Was the wine somehow stronger here? She seldom drank more than a glass at a time at home.

It was as Charles paid the bill – at his insistence – that his hand brushed her own. Surely an accident? He then told her she looked beautiful, laughed it off and said, ‘Now, what would Mr Anstice say?’

As May wrote under her maiden name, there was no Mr Anstice (and even if there had been a ‘Mr Anstice’ he was no longer of the slightest concern to her). Her book blurb, of course, still mentioned her husband.

She was about to confide all this when a slight movement outside caught her eye. There was the ubiquitous Diogo, balanced on the roof of a tiny candy-coloured cabin intended to represent a traditional Madeiran house. He was trying to twist fairy lights among the branches of a large plant with pendulous white flowers which appeared to change to pink as they aged. ‘Oh look!’ she said.

At that moment Diogo lost his footing and disappeared from view, almost knocking over a camera-laden tourist as he did so. Charles looked out of the window and apparently saw only the tree and the lights. ‘Oh yes. They decorate for Christmas here every year. Pretty lights everywhere. Employs half the island. You’ll just miss the big switch-on, that’s a shame. Can’t you stay a bit longer?’ Again, his hand brushed hers. This time she was less sure it was accidental. She drew back from him a little. What was she thinking? He was a chance acquaintance, no more, and she was behaving like a schoolgirl.

‘I really meant look at the plant,’ she said, trying to distance herself from his burgeoning familiarity.

‘That? Oh it’s just a brugmansia. Very beautiful and all that, but really rather deadly. Be very wary.’ May stood, and clung to the back of her chair, dismayed at how unsteady she felt. She really should not have accepted the large glass of Madeiran rum poncha which Charles had suggested to round off the meal.

‘I must see you safely back to your hotel, May,’ murmured Charles, his soft hand now firmly holding her elbow. ‘Remind me where it is you’re staying?’

She had not told him about the apartment and was suddenly glad she had not. Halfway across the Esplanade, only the café lights still lit up the darkness. Diogo was barrowing the folded umbrellas into the store at the back of the building. He stopped and stiffened when he saw Charles and May approaching. Charles said something sharp in Portuguese and Diogo was about to reply when his uncle barked an order and he turned back for the bar.

‘Diogo, wait!’ May grasped at the lifeline. ‘Charles, do forgive me. I really think I have had a bit too much to drink. I’m not used to it. I’ll stop here for a coffee, if you don’t mind, just to clear my head. It’s been such a lovely evening. Thank you.’ With that, she sat down.

Charles recovered well, but not quite fast enough: she had seen the brief flicker of anger, quickly masked by concern. ‘In that case I shall enjoy one with you, my dear May, and then see you safely back.’ He sat down beside her. Damn.

May looked, she hoped desperately, towards Diogo at the bar. The young waiter soon returned with a tray holding two cups of coffee, both black, plus the jug of frothy milk. He placed the cups on the table and lifted the jug with a theatrical flourish, then appeared somehow to trip over the table leg and lose his balance. May watched as the jug of scalding milk emptied itself instead into her dinner companion’s crotch.

A stream of unexpectedly fluent Portuguese escaped Charles’ lips, which brought Diogo’s aunt Ana scurrying to see its cause. She shouted at the boy for his clumsiness and even in Portuguese May could tell she was saying that Diogo was lucky his uncle was not present. Diogo made apologetic noises to May, to Charles and to his aunt, all the while maintaining steady and reassuring eye contact with May, until the old lady hustled him back behind the bar. Charles was sponging his trousers with a napkin which was now, May saw, staining his expensive khaki chinos blue.

All at once May felt a wobble of guilt. They had had a nice time, hadn’t they, until they had left the restaurant? And he had paid for dinner. Perhaps Charles was just lonely and had come on a bit too strong. And wasn’t she lonely – and more than a bit drunk – herself? She fiddled, awkwardly, with her wedding ring.

Charles, still dabbing his ruined trousers, made his apologies. ‘Such a lovely night ruined by that idiot boy. I must go and change. Shall we meet tomorrow to make amends? Coffee perhaps, but not here, clearly. 11ish? Where shall I call for you?

She searched for a polite way to say no and failed, but did at least avoid telling him the location of her apartment, agreeing instead to meet him on the corner of the park by a statue the following day. I can always not be there, she thought, watching him depart with considerable relief.

Diogo was swiftly at her side, his aunt still watching his every move. ‘Thank you,’ she croaked, her eyes filling with tears. Drat it, she really was drunk. Get a grip!

‘No. No. Senhora. Wait, I bring you more coffee. All is well. This man is go now.’

So he had understood her predicament. ‘Thank you. Do you know Mr Hamilton?’ Diogo shook his head. ‘My uncle and aunt, they, they know this man.’ Could she detect a warning in his words?

‘Does he live nearby?’

He nodded. ‘I think. He is here most every day.’ His aunt said something else and he smiled. ‘My aunt say I must bring you safe to your house when I finish.’ Old Ana smiled her own confirmation from behin the counter. May felt gratitude flood her.

Some time past midnight, once the cafe was secure, Diogo walked beside May for the short distance to her street door. ‘You have key?’

She showed it to him. ‘Thank you, Diogo. I’ll see you all tomorrow I expect.’ She tried not to slur her words, feeling foolish. Once inside, she turned and waved to him through the glass as he walked away.

In the lift she still felt a little queasy. When it stopped she stumbled across the landing to her door and pushed the key into the lock, where it chose that moment to refuse to budge. It had been stiff before, drat it. She rattled it, pulled it out and pushed it back in again but still it would not turn. She was just wondering if she could possibly wake the old porteira at this hour when suddenly her blood ran cold. There were voices. Coming from inside her apartment. She took a step backwards, the key still in her hand as the door opened, just a crack. A stream of Portuguese invective flooded out of the dark hallway within. Oh God. Oh no. Wrong floor. Wrong bloody floor. And of course all the floor layouts in the block must be identical!

Then someone switched on a light inside the doorway and illuminated its occupants.

‘Guten abend, sweetie,’ said the blonde boy behind him, one languid hand resting possessively on the shoulder of another man. A man who said ‘oh hell!’ Just seconds later. It was only once May had stammered her apology and fled back into the sanctuary of the lift that she realised both Charles and his German friend had been clad only in rather inadequate hand-towels.

May now pressed the 4th floor button instead of the 2nd. She tumbled in through the door of her own apartment, slamming it and bolting it behind her. Gasping against its security for some moments, she tried to work out what on earth had just happened. Then she went to the fridge, poured more orange juice with a shaky hand, and again opened the window overlooking the park. As the cool air slowed her pounding heart, she felt unexpected and uncontrollable laughter rise up through her throat and erupt into the Madeiran night. She laughed until tears rolled down her cheeks, great healthy sobbing gusts of hilarity, and thought: that was a narrow escape. Although from what, she was not yet certain.

When she heard the indignant window slam two floors below her, it set her off all over again.

When Milly rang May towards the end of her stay to ask how she had fared, the incident with Charles already seemed like ancient history. She had not seen him again in the apartment block at least. Sitting at the café as she waited for her airport taxi, she was conscious of babbling with enthusiasm about her holiday.

She told Milly all about Diogo and the café and Diogo’s new wife (he had shown her a photograph of his identical twin boys).

Then there was the trip May had taken high through a rutted and thrilling mountain pass in a jeep driven by Diogo’s cousin, all the way to Porto Moniz through ancient laurel forest and down to the rugged coastline beyond.

She raved about the food too: bolo do caco bread, the fruit (she had developed a weakness for custard apple and passionfruit) and even the scabbardfish with local fried banana which Diogo’s aunt cooked to perfection.

The apartment – full of original art and with every possible home comfort – had become a true home from home.

On her last day she had visited the botanic gardens of Madeira, high above Funchal, taking the rickety bus up the steep route rather than the more popular cable car overhead. After a morning spent idling through the terraces and parterres, it was there of all places that she suddenly spotted Charles at a café table, in earnest conversation with a tearful young woman. Struck by a thought, she looked around and, sure enough, not far away, was a familiar tall, blonde German tourist wielding a camera with a very long lens: apparently engrossed in photographing a tree fern – but in reality, doubtless, capturing every intimate moment of the encounter.

God. They must have thought they had struck paydirt when Charles had bumped into May after the bookfest. May was not exactly famous but certainly well known. How much would she have paid to prevent a ‘Mr Anstice’ – or the literary press – from seeing a compromising photograph of her with Charles during a drunken coupling? How much had others paid before her?

And, she reflected, how very awkward indeed for Diogo and his family if the dodgy Charles (if that was his name) were local, and a regular café customer.

May did not hesitate this time. She walked over to the young German and waggled her finger straight into his lens, startling him. He scuttled off at gratifying speed. Then she strolled over to his partner in crime, who had his back turned, and was, she saw, clasping the hand of his latest intended victim as he gazed into her eyes. ‘Oh there you are, Charles darling,’ May trilled into his appalled face. ‘I have to pop home now, so could you just pick up some cereal – for the twins – when you’ve finished here?’ She then turned on her heel with a flick of her golden dress and left them both, without waiting to see the impact of her actions. She had given the girl a chance. It was up to her now.

‘Well. You sound much better,’ said Milly on the phone. ‘Not brooding over Malcolm any more, then?’ May just laughed. She had honestly not thought of Malcolm and Geraldine once since her first visit to the café. She had just thrown a few illicit bits of stale bread to the muscovy ducks on the fountain pond and, as an afterthought, had tossed her wedding ring in after it.

She told Milly that when she got home she planned to put her house on the market. A move was in order. She could go anywhere, live anywhere. She was free.

‘You’re better off without the jealous bastard anyway,’ snorted Milly. ‘He never could bear you earning more than he did.’

Was that it? Was that really it? The final trace of shadow over May’s heart detached itself and evaporated into the clear Madeiran air.

‘And,’ added Milly, as May knew she would, ‘Dare I ask if the muse has struck?’

At that moment Diogo brought May one last coffee, another tiny pastel de nata nestling on the saucer. She smiled up at her friend. ‘Do you know, Milly, I think it has. Thank you, Diogo. Obrigada, Madeira.‘

All characters in this short story are entirely fictitious. All the places are entirely real, including the apartment in the Residence Arriaga where Vee stayed. Feedback most welcome

You are welcome to share this story to friends and family if you have enjoyed it, but please remember it remains her copyright and no commercial use is permitted.

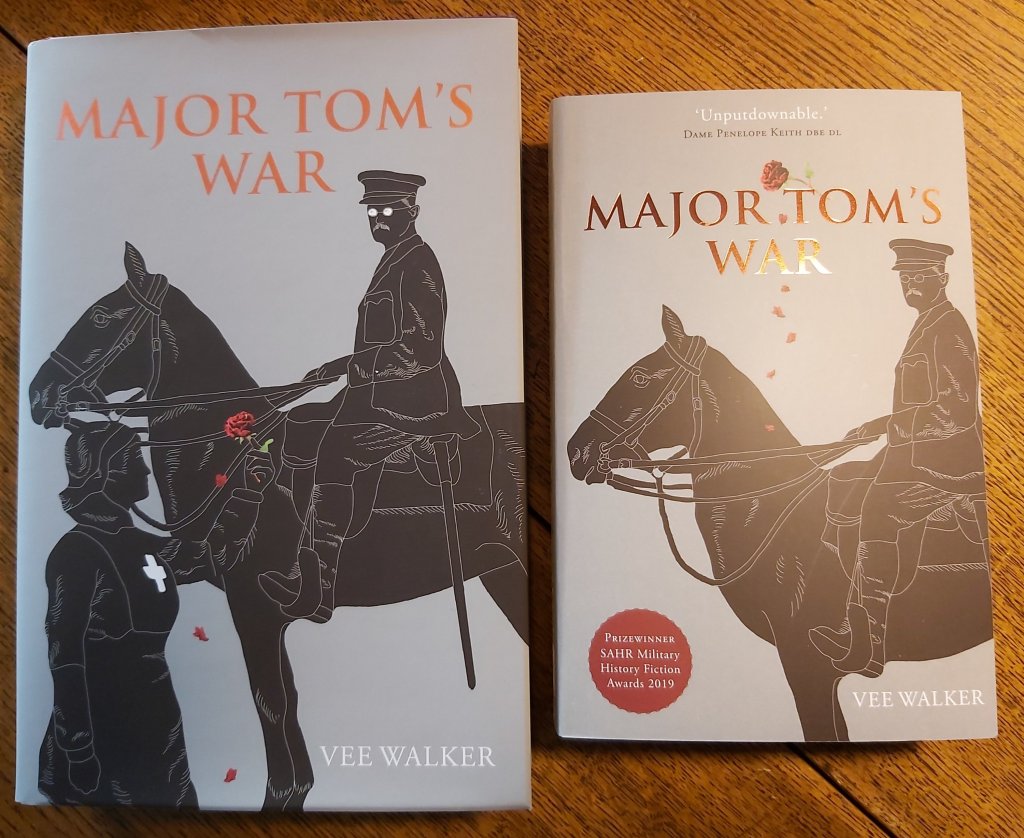

Vee Walker is an author based in the Black Isle in the Scottish Highlands. Her prizewinning WWI love story Major Tom’s War is going down a storm with book groups worldwide. It is available in paperback, ereader and hardback from its publisher http://www.kashihouse.com and from all good booksellers everywhere.

(C) Vee Walker 2021